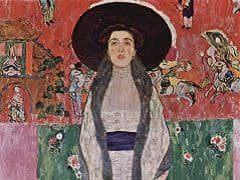

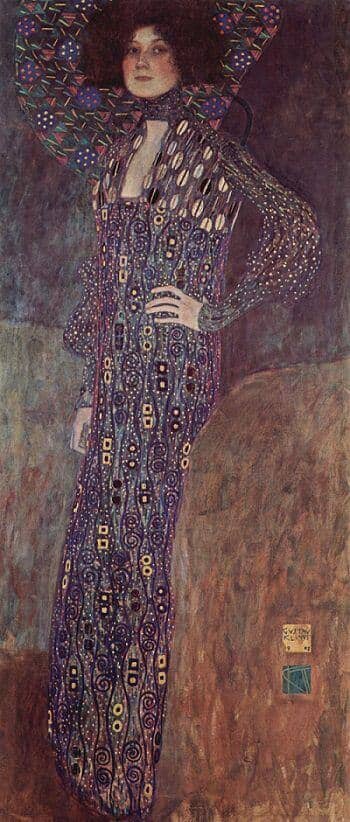

Portrait of Emilie Floge, 1902 by Gustav Klimt

Even during Klimt's lifetime, it was widely assumed that he and Emilie Floge were lovers, yet the truth of the matter, like many things concerning fin-de-siecle sexual mores, may be considerably more

complex. Emilie Floge, twelve years Klimt's junior, was the sister of his brother Ernst's wife. When, some fifteen months after his marriage, Ernst died, Gustav was appointed guardian of the couple's

newborn daughter. In this capacity, he had free reign in the Floge household and became something of a surrogate uncle to young Emilie. The surviving correspondence between the two is voluminous, yet

entirely platonic; their "trysts" involved such innocent activities as French lessons. Would the family have tolerated Klimt's presence in their summer home on the Attersee, as they did almost every

year, had the two been clandestine lovers? And would Klimt so openly have paraded his mistress at the theater and opera, as he did Emilie? Klimt's real lovers, as is now known, were not such nice,

middle-class ladies, but models and charwomen. If Emilie was the love of his life, she was a pure and sacred love, a Madonna to the whores who, figuratively and literally, occupied the dark alleys

offin-de-siecle sexuality.

It is perhaps no wonder that Klimt's Portrait of Emilie Floge, painted in 1902, was the first to present its subject as a bejeweled icon, a gilded beauty whose decorative trappings constitute a

metaphorical chastity belt. Directly anticipating the "gold" portraits of 1906-1907, the picture was exceedingly radical for its day, and perhaps for this reason neither Emilie nor her family liked it.

The Floges declined to hang the painting, and in 1908 it was acquired by the City of Vienna. It was Emilie's fate also, in the end, to be rejected. In 1904, she and her sisters, Helene and Pauline, had

opened a fashion salon, smartly outfitted by the Wiener Werkstatte, in Vienna's Casa Piccola. This entrepreneurial venture (unusual for women at the time) was necessitated by the financial decline of

the once-prosperous Floge family, and by the fact that the sisters, in their thirties, were too old to be considered reasonable marital prospects. Klimt, with all his avuncular affection, would not

marry Emilie, preferring to retain his freewheeling bachelor's existence.

Despite Klimt's notorious philandering, Emilie remained true to him not only throughout his life, but also thereafter; she never married. Even after the Nazi Anschluss in 1938 forced the closing of the

fashion salon, she maintained a "Klimt room" on its premises, in which stood the artist's easel and his massive cupboard, housing his collection of ornamental gowns, his caftanlike painter's smocks,

and several hundred drawings. The doors of that room were always kept bolted.